Mountain Men Fur Trade Exploration History

By

Ned Eddins

Alexander Mackenzie Manuel Lisa Andrew Henry Donald Mackenzie

North West Company Hudson’s Bay Company Trapping Furs Indian trade Goods

Trade and Intercourse Act Fur Trade Area Statistical Review

Early North America history centers around the animal skin trade. North of present day Mexico, the vast territory of the United States and Canada was explored, wars were fought, and Indian cultures destroyed in the pursuit of beaver skins and buffalo hides. Despite the European fur trade encompassing a wide variety of fur bearing animals, mountain men and the mountain man rendezvous are virtually synonymous with beaver. The vast majority of the beaver pelts were sent to England for making hats. For well over two centuries in Britain and Western Europe the beaver hat defined style. From the early 1600s to the mid-1830s, if it was not a beaver, it was not a hat–but merely something to cover one’s head (Neander 97).

Canadian fur traders and Mountain Men in search of beaver were the major explorers of North America. In addition to the economic benefits of the fur trade, Mountain Men were a major factor in determining the boundaries of the United States, especially the Pacific Northwest. Fur traders from the Mountain Man-Indian Fur Trade era not only discovered the Oregon and California trails, they provided the guides for America’s western expansion over the Oregon and California trail.

Native American Indians were the major source of beaver pelts and buffalo hides, for the Canadian, Great Lakes, and upper Missouri River fur trade from the late 17th to the early 19th century. During most of this period, Native Americans used nets, snares, deadfalls, clubs, etc. to obtain beaver pelts.

The glamour of the mountain man rendezvous and the search for beaver pelts by the mountain men of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Era obscured the “bread and butter” of the fur trade. The staples of the fur trade were muskrat, raccoon, fox, deer hides, and later buffalo robes. At a New York fur auction, John Jacob Astor sold upwards of half a million muskrat pelts in one day. Mountaineers, Indians, and the early settlers traded these furs and hides by the millions.

For many colonial settlers, the only source of “cash money” was furs and hides. An early frontiersmen, Daniel Boone was a long hunter. The principal goal of the Long Hunters was deerskins. Depending on its size and quality, a doe hide was worth fifty cents or more. The skin of a buck brought a dollar and up, hence the term “buck” as slang for currency. Small bands of long hunters brought back several hundred, sometimes even a thousand skins in a season. By the end of the War of 1812, the American tanning industry was a twelve million dollars business (Lavender).

Please Note: There have been several emails against the trapping of fur bearing animals. If the people had read the Mountain Man-Indian fur trade articles, they would know this site is not about trapping. The Mountain Man-Indian Fur Trade site is concerned with the history of the fur trade. Still, the trapping of fur bearing animals was key to the mountain man era and played a significant role in America’s western expansion.

By the late seventeen hundreds, Plains Indians were exchanging beaver pelts and horses to the Hudson’s Bay and North West fur traders for European goods. These trade fairs were held at the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara villages on the Missouri River. The major items exchanged were:

garden products (beans, squash, corn, etc.) raised at the Missouri River villages.

horses, furs, buffalo hides from the Plains Indians.

whiskey, guns, iron goods, trade beads, and a few beaver traps from Canadian traders.

By the mid-eighteen hundreds buffalo hides dominated the Indian fur trade. The demise of the large buffalo herds is often blamed on the white man, but Indians contributed a great deal to it as well.

The topography of Canada and the United States west of Lake Superior and north of the forty-second parallel was basically determined between 1793 and 1812. With the exception of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, fur trader-explorers from the American and Canadian fur trading companies did all of the early exploration. These trader-explorers were either accompanied by Native Americans, or Native Americans told them about the major passes and routes through the Rocky Mountains.

Lewis and Clark:

President Jefferson read Mackenzie’s book and realized the need to speed up the timetable for the launch of Lewis and Clark’s Voyage of Discovery to the mouth of the Columbia River. President Jefferson’s instructed Lewis and Clark to make note of fur-bearing animals, the attitude of Indians to the fur trade, and determine a practical water course across the continent. President Jefferson hoped this route would serve as a more practical route for the western fur trade than any the British could establish to the north.

Astorians:

John Jacob Astor was behind the next group of men to cross the continent. Many historians and Internet writers infer John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company was a dismal failure. In a two and a half-year period, the Pacific Fur Company lost sixty-one men, the Tonquin, and thousands of dollars on the sell of Fort Astoria to the North West Company in November of 1813. If this is all you consider, it was a dismal failure, but in terms of the United States northern boundary and America’s western expansion, it was a resounding success. Within in a two year period, the Astorians established trading posts on the Columbia, Willamette, Okanogan, Spokane, and Snake rivers. These fur trading posts, especially Okanogan, were a major factor in the State of Washington being part of the United States. The Pacific Fur Company had a profound affect on America’s western expansion and Manifest Destiny. Except for a detour in western Wyoming, the trail of Robert Stuart and six Astorians over South Pass to St. Louis was the basic route used by Americans to reach the Oregon Territory. The “dismal failure” of the Astorians provided the Oregon Trail leading to America’s Manifest Destiny for several hundred thousand Oregon and Mormon pioneers and the California gold seekers.

North West Company:

Founded in 1779, by a group of Montreal Scottish-Canadian traders, the North West Company defied the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Royal Charter. With the exception of the Montreal managing partner, the company partners wintered in the “pays d’en haut”…the country beyond Lake Superior. The company men that live and work there were known as the North Men. By 1784, nine different fur trading groups had joined the North West Company. Consolidated into one firm, the North West Company became the Hudson’s Bay Company’s most powerful rival.

The Montreal based North West Company was different from Hudson’s Bay Company in significant ways. The company was owned and operated by partners active in the fur trade; most of the partners lived and worked in the pays d’en haut. These North Men, or “wintering partners”, had a personal stake in the company’s success.

Unlike the sedentary Hudson’s Bay men, the North West Company expanded its operations to Lake Athabasca and constructed posts in the Oregon Country. Provisioned with pemmican from the plains, canoe brigades brought up to 20,000 beaver plews to an annual rendezvous on Lake Superior at Grand Portage, and after 1805, at Fort William near present day Thunder Bay, Ont. The managing partner in Montreal kept in contact with the North Men through a mail system that went to the North West Company posts twice a year.

In contrast, Hudson’s Bay Company directors and investors were primarily English noblemen and financiers, who governed the Company from England. The Hudson’s Bay Company partners had little actual knowledge of the fur trade, or the country they controlled.

Growing hostilities between the two fur trading companies were acerbated by proposed settlements around the junction of the Assiniboine and Red rivers. In 1812, the Hudson’s Bay Company gave Lord Selkirk a land grant of 116,000 acres in the Red River Valley. The Métis that lived in this area were farmers, fur traders, and hunters that produced pemmican for the North West Company’s canoe brigades. When Lord Selkirk opened the area for settlement, the surveyors and settlers did not recognize the Métis land claims. The Métis and the North West Company formed a powerful alliance against the Hudson’s Bay Company that led to open hostilities.

On March 26, 1821, a Parliamentary Act basically forced the consolidation of the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies under the Hudson’s Bay Company name. The Hudson’s Bay Company name, charter, and privileges provided a foundation for the new firm. Chief Factors and Traders for the new company were chosen from both organizations and given shares based on their ability. The majority of these men were from the North West Company.

Alexander Mackenzie:

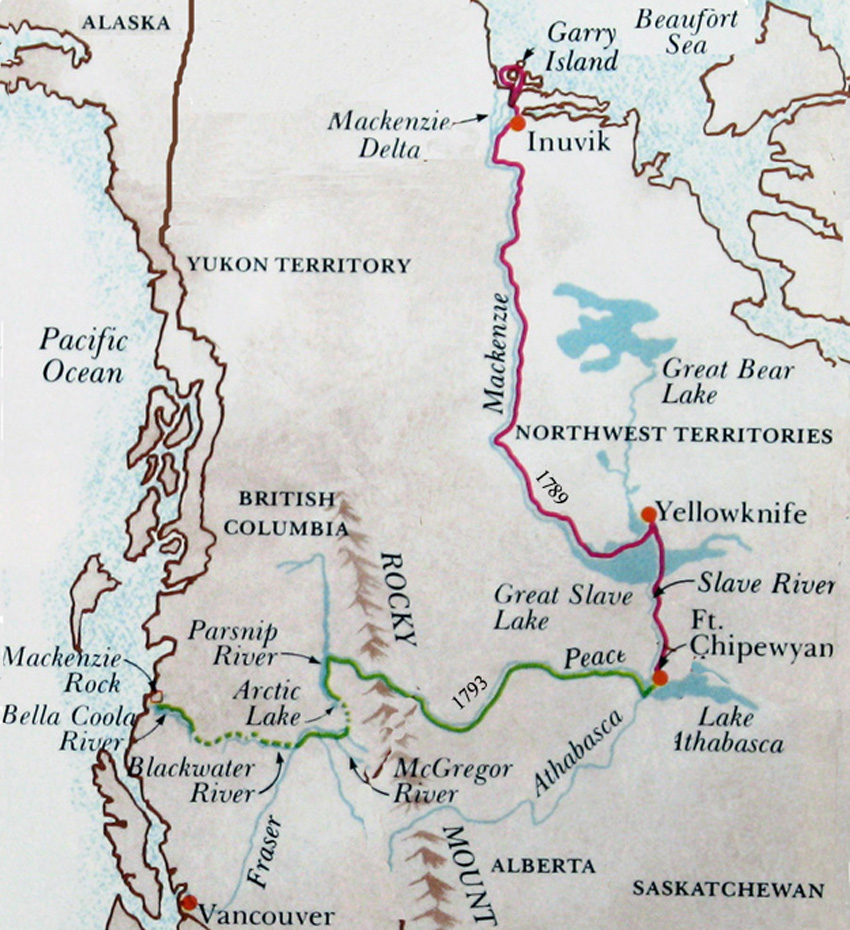

Alexander Mackenzie 1789-1793

In 1789, Alexander Mackenzie, a North West Company partner, explored the Mackenzie River from the Great Slave Lake to the Arctic Ocean. Four years later (1793), Mackenzie made the first successful crossing of North America. Accompanied by Alexander McKay, six French Canadians, two Indians, and a Newfoundland dog, Mackenzie left Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca in 1793. The fur traders followed the Peace River to the Parsnip River, and then up the Parsnip to the Continental Divide. After an eight hundred and forty-step portage to a lake, Mackenzie believed he had reached the headwaters of the Columbia River; actually it was the Fraser River. A couple of hundred miles downriver cataracts and falls made the waterway impassable.

Carrier Indians told Mackenzie the river could not be traveled by canoe, and when two Carrier Indians offered to guide them, the expedition headed cross-country toward the Pacific Ocean. Reaching the Bella Colla River, the expedition followed it to the Pacific coastline. While waiting at Dean’s Inlet for a clear day to determine the longitude and latitude, Mackenzie used vermilion in melted grease to write on the rock. He wrote:

Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by Land, the twenty-fecond of July, one thoufand feven hundred and ninety-three.

After his return from the Pacific, Mackenzie met with Simon McTavish, head of the North West Company, and suggested that if the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies would join forces, they could control the northwest fur trade above Spanish California. Rebuffed by McTavish, Mackenzie went to England to meet with leaders of the Hudson’s Bay Company. While in England, King George III knighted Alexander Mackenzie. Before returning to Canada, Sir Mackenzie wrote a book on his travels titled, Voyages from Montreal on the River St. Laurence.

David Thompson:

David Thompson arrived on the shores of Hudson Bay in 1784. At that time, the interior of North America was basically unknown. By the time David Thompson, a fur trader and a surveyor for Hudson’s Bay and then the North West Company,left the Northwest country in 1812, he had accurately mapped the main routes of travel and delineated the physical features of approximately 2.3 million square miles of Canada and the northern area of the American territories west of Lake Superior.

Donald Mackenzie:

From 1818 to 1821, Donald Mackenzie, a brigade leader for the Canadian North West Company and a former Astorian, led yearlong trapping expeditions from Fort Nez Perce at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers into the upper Snake River country.

Dr. Dale Morgan wrote about Donald Mackenzie:

The bold and imaginative use of Mackenzie’s men for trapping rather than for manning trading posts; his system of supply and the transport of his furs, which involved the use of horses in place of the boats to which the fur trade had been wedded; his maintenance of his trapping force in the field almost uninterruptedly for three years–all this displayed genius and laid the groundwork for the revolution which Jedediah Smith and his associates were about to effect in the conduct of the American fur trade.

Approaching from the west, Canadian trappers from the North West Company’s Snake River Brigade named three distinctive peaks the Trois Tetons (three breasts)…the Teton Range can be regarded as the geographical center of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade rendezvous system

.

There is evidence at least some of North West brigade trappers entered the thermal areas of Yellowstone (Mattes).

North West Company’s Snake River Brigade led by Donald Mackenzie trapped the Green River Valley of Wyoming three years before Jedediah Smith and the Ashley trappers arrived there (Morgan). Peter Skene Ogden was the brigade leader in 1825 and had a confrontation with Johnson Garder over whether British or Americans owned the land…neither did they were in Mexican territory.

Hudson’s Bay Company:

Hudson’s Bay Company was formed on May 6, 1670, making it the oldest corporation in the world. It was given all the land whose rivers drained into Hudson Bay. This area became known as Rupert’s Land. The Hudson’s Bay charter gave them control over what was at the time the tenth largest country in the world. Hudson’s Bay Company controlled most of the land in modern day Canada between the Continental Divide and the St. Lawrence River drainage, and as far south as South Dakota. Trappers competing against Hudson’s Bay claimed the initials HBC stood for “Here Before Christ”.

After the amalgamation of the North West and the Hudson’s Bay Companies in 1821, the headquarters for the Snake River Brigades was moved to Flathead House near Thompson Falls, Montana. From 1822 to 1824, Michel Bourdon, Finan McDonald, and Alexander Ross led large Hudson’s Bay brigades of trappers from Flathead House into the central Rockies. These Canadian fur trade brigades trapped the Bear River drainage and the Green River Valley of Wyoming. Following the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company merger in 1821, the head of the Hudson’s Bay Company, George Simpson, instituted a “scorched earth policy”. Simpson reasoned if the beaver were gone, there would be no reason for Americans to go to the Oregon Country. The Hudson’s Bay fur trapping brigades succeeded in the “scorched earth policy” to the point beaver become nearly extinct in the Snake River drainage system. This “scorched earth policy” was not the customary policy of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Normally, the Company practiced strict conservation policies. Trapping brigades were prohibited from returning to a stream for a two to three year period after the area was trapped. Modern day studies show, if disease or habitat destruction is not a factor, beaver repopulate a depleted watershed within a three to five year period (Neander 97).

Dissatisfied with the results of the Snake River brigades, George Simpson placed Peter Skene Ogden in charge of the Snake River fur trapping expeditions of 1825.Under Ogden and then John Work the Snake River brigades departed from Fort Vancouver, Fort Nez Perce, or Flathead House early each fall with approximately one hundred men and three hundred horses. Under Ogden, many of the Iroquois and Delaware trappers in the brigades took their families with them.

Trade and Intercourse Acts:

The colonial fur trade, and later the mountain man fur trade, had a pronounced effect on Native American Indians. The federal government tried to protect the American Indians from land speculators, fur traders, and eventually the mountain men and the suppliers of the mountain man rendezvous through the Trade and Intercourse Acts. These acts are often referred to as the non-Intercourse acts:

Beginning in 1790, Congress passed a series of laws to regulate the purchase of Indian lands and the Mountain Man-Indian Fur Trade. These laws were renewed every two years until 1802 when they were made permanent. The basic outline of the Federal Indian Policy was formed by the Trade and Intercourse Acts (Avalon Project).

No person shall be permitted to carry on any trade or intercourse with the Indian tribes, without a license – term of license not exceeding two years.

No citizen or inhabitant shall trespass on Indian lands, make a settlement on lands belonging to any Indian tribe, or shall survey such lands, or designate their boundaries, by marking trees, or otherwise, for the purpose of settlement, he shall forfeit a sum not exceeding one thousand dollars, nor less than one hundred dollars, and suffer imprisonment not exceeding twelve months.

No purchase or grant of lands, or of any title or claim thereto, from any Indians or nation or tribe of Indians, within the bounds of the United States, shall be of any validity in law or equity.

No person shall be permitted to purchase any horse of an Indian, or of any white man in the Indian Territory, without special license for that purpose.

It shall and may be lawful for the President of the United States, to cause them to be furnished with useful domestic animals, and implements of husbandry, and also to furnish them with goods or money, in such proportions, as he shall judge proper, and to appoint such persons, from time to time, as temporary agents, to reside among the Indians.

This last provision of the Trade and Intercourse Acts instituted the Factory System of government trading houses. These posts were established to supply quality merchandise at a fair price in exchange for Indian furs. An unstated goal of the factory system was to make the Indians dependent upon the United States government. In other words make it easier for the government to acquire Indian lands.

President Jefferson proposed placing restriction on the Mountain Man-Indian liquor trade. A law prohibiting the sale, or trade, of liquor to Native Americans was passed on March 30, 1802. The law of 1802 did not have the desired effect and a stronger law was passed in 1822. Neither of these laws prevented the fur traders from carrying whiskey for the use of boatmen going to the mountain man rendezvous. Finally in 1832, Congress bluntly declared: No ardent spirits shall be hereafter introduced, under any pretence, into the Indian country (Pruhca).

This was all well and good, but who enforced the laws on the fur traders and mountain men at the mountain man rendezvous. Supplying Indians with alcohol was not the only laws broken at the mountain man rendezvous. Mountain men were trespassing on Indian Territory, which was prohibited by the Trade and Intercourse Acts, and six mountain man rendezvous were held south of the forty-second parallel in Mexican territory.

Manuel Lisa:

Manuel Lisa, field trader of Lisa, Menard, and Morrison Fur Company, established a fur trading post at the junction of the Bighorn and Yellowstone rivers in November of 1807. This was the first organized trading and trapping expedition to ascend the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains (Oglesby). Located on the left bank of the Bighorn River, Fort Raymond (Fort Ramon, Manuel’s Fort) was the first American trading post built in the Rocky Mountains.

Not long after arriving at the mouth of the Bighorn River, Manuel Lisa dispatched three men to visit the Crow Indian villages: John Colter to the Stinkingwater (Shoshone) and Wind river villages; George Drouillard to the Bighorn and Powder river villages; Edward Rose to the Tongue River villages. The fur trappers carried word of a trading post at the mouth of the Bighorn River for the Crow Indians spring fur and hide trade. During his travels, John Colter entered what would be Yellowstone National Park, but the mountain men did not refer to the Yellowstone area as Colter’s Hell. The mountain man’s Colter’s Hell was a thermal mud pot area at the junction of the North and South Stinkingwater rivers near Cody, Wyoming…not Yellowstone National Park.

Lisa, Menard, and Morrison took on new partners and become the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company in 1809, and in 1812, the name was changed to the Missouri Fur Company. Astor’s American Fur Company, founded in 1808, and the Missouri Fur Company confined their activities to the Missouri River watershed. The War of 1812 and the following economic depression put a damper on the fur trade for the next ten years.

Andrew Henry:

Andrew Henry was a partner in the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company. Henry went upriver with Pierre Menard in 1810 to the Three Forks area of Montana. A few weeks after arriving there, Blackfeet warriors forced Menard to take most of the men back to Fort Raymond at the mouth of the Bighorn River. Andrew Henry with sixty trappers remained at the Three Forks. Constant harassment by Blackfeet Indians forced Henry and his trappers to leave the Three Forks area.

In late July of 1810, Andrew Henry and his trappers went up the Madison River. Crow Indians stole the majority of Henry’s horses near Reynolds Pass on the Continental Divide. Without packhorses horses, Henry and his men reached the Snake River area with little more than what they could carry on their backs. Neither Andrew Henry, nor any of his men, left a description of the winter at Fort Henry, however, an article in the October 16, 1811, issue of the Missouri Gazette stated:

…The group [Henry’s party] wintered on what has since been called “Henry’s Fork” of the Snake River, a beautiful country, well stocked with beaver, but had the misfortunes to be involved in a most severe winter, with deep snow and bitter cold keeping game from the area, ultimately forcing the men to subsist a large part of the time on roots…

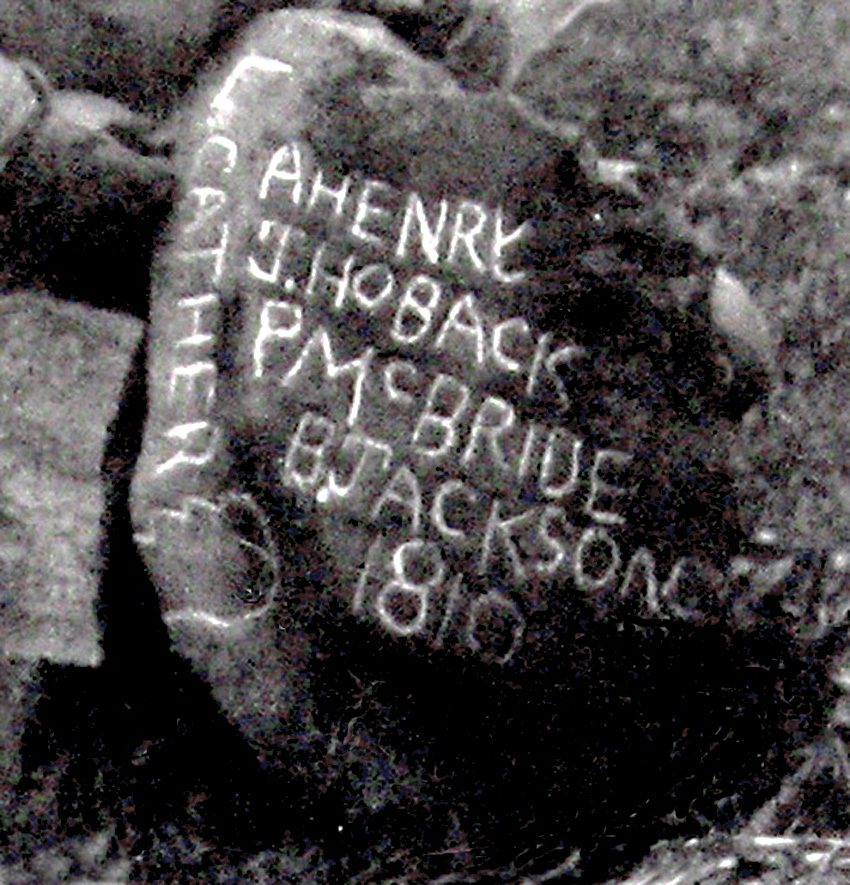

During a winter as described by the Missouri Gazette, veteran mountain men would camp in a protected area with beaver and game, not on the windblown plains of the upper Snake River Valley. The winter encampment of Henry’s men is referred to as Fort Henry. Fort Henry is credited with being the first American post west of the Continental Divide. History places the fort near Elgin, Idaho, on the Henry’s Fort of Snake River, but there is evidence Henry and his men were on Conant Creek rather than on Henry’s Fork. At the Conant Creek site is an inscribed boulder with names on it.

Log and brush shelters, as well as, shallow caves along the bank of Conant Creek offered Henry and his men enough protection to survive a severe winter. A former owner of the Conant Creek site told the author, that when he was a boy, dugout caves were visible along the creek bank.

As soon as the mountain passes were crossable in the spring of 1811, Henry’s disheartened, starving men split off in different directions. A deranged Archibald Pelton wandered in the mountains two years before Astorians found and took Pelton to Fort Astoria. Some of the Henry men headed for Spanish settlements thought to be a few weeks journey to the south. Three of Henry’s trappers, John Hoback, Jacob Rezner, and Edward Robinson went through Jackson Hole and over Togwotee Pass to the head of the Wind River. From the Wind River, the three trappers crossed the Owl Creek Mountains to the Bighorn River. The three trappers followed the Bighorn to the Yellowstone River and down it to the Missouri River.

Andrew Henry with a few men retrieved the beaver pelts from caches in the Three Forks area and then floated the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers to Fort Manuel near the Mandan villages.Andrew Henry returned to St. Louis in the fall of 1811. In 1822, Andrew Henry and William Ashley formed the Ashley-Henry Fur Company to trap the upper Missouri River country. Andrew Henry left the fur trade in 1824.

Trapping Fur :

Spring and fall were the season for prime beaver pelts. Mountain men frequently traveled to the areas selected for the hunt in brigades of thirty to forty trappers. Once there, the trappers set out in parties of two to four to set their traps in the streams. If it was a party of four, there would usually be two trappers and two camp tenders.

Beaver traps were checked night and morning. Once the beaver were caught, they were skinned, dried on a hoop, and then folded in half with the fur to the inside. Sixty pelts were pressed into a bundle for hauling back to St. Louis. On average, a dried beaver plew weighed one and a half pounds. Sixty beaver pelts, pressed and tied together weighed approximately ninety pounds–the standard beaver pack.

Osborne Russell in his book, Journal of a Trapper, gave a description of the typical mountain man:

A Trappers equipment in such cases is generally one Animal upon which is placed…a riding Saddle and bridle a sack containing six Beaver traps a blanket with an extra pair of Moccasins his powder horn and bullet pouch with a belt to which is attached a butcher Knife a small wooden box containing bait for Beaver a Tobacco sack with a pipe and implements for making fire with sometimes a hatchet fastened to the Pommel of his saddle his personal dress is a flannel or cotton shirt (if he is fortunate to obtain one, if not Antelope skin answers the purpose of over and under shirt) a pair of leather breeches with Blanket or smoked Buffalo skin, leggings, a coat made of Blanket or Buffalo robe a hat or Cap of wool, Buffalo or Otter skin his hose are pieces of Blanket lapped round his feet which are covered with a pair of Moccasins made of Dressed Deer Elk or Buffaloe skins with his long hair falling loosely over his shoulders complete the uniform.

Joe Meek gave this account of the mountain man’s winter quarters.

This was the occasion when the mountain-men “lived fat” and enjoyed life a season of plenty, of relaxation, of amusement, of acquaintanceship with all the company of gayety, and of, “busy idleness.” Through the day hunting parties were coming and going, men were cooking, drying meat, making moccasins, cleaning their arms, wrestling, playing games and in short everything that an isolated community of hardy men could resort to for occupation was resorted to the mountaineers. Nor was there wanting in the appearance of the camp, the variety and that picturesque air imparted by a mingling of the element for what with their Indian allies, their native wives and numerous children. The mountaineers camp was a motley assemblage, and the trappers with their affectation of Indian coxcombry [conceited dandy] the least picturesque individuals.

Meek’s description is a little over done. Hunting elk in weather like pictured above would not be “joyous”. On several occasions, the mountain man winter camps were moved because of extreme cold and lack of game in the area.

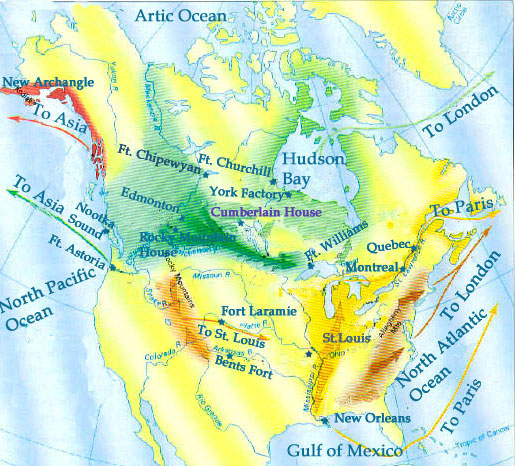

Fur Trade Area:

The Canadian fur traders in the northwest trapped the watershed of Columbia, its major tributary the Snake River, part of the Great Basin, and into the Green River Valley. The Taos fur traders trapped the Arkansas and Rio Grande valleys of Colorado and the Salt and Gila rivers of the Southwest. The Rocky Mountain fur traders centered their operations in the Green River Valley and from there to the headwaters of the Missouri, Colorado, Snake, Columbia, and the northeastern section of the Great Basin. The areas trapped by the various fur companies overlapped and on occasion led to conflict between the fur trappers.

The great river systems…the Missouri, the Snake and the Green River of the Colorado…drained the major fur trade area of the Rocky Mountains. The territories drained by these rivers had a direct bearing on the territorial expansion of the United States. The Missouri River and its tributaries established the upper Louisiana Territory as being below the forty-ninth parallel. Settlement of the Oregon Territory boundary in 1846, gave the United States the watershed of the lower Columbia and the Snake rivers. Besides California, a major portion of the 1847 cession from Mexico was in the valleys and tributaries of the Colorado River.

The largest tributary of the Colorado, Columbia, and Missouri rivers heads within a sixty-eight mile radius of the Grand Teton peak on the western Wyoming border. Another circle with a radius of one hundred and ninety-one miles covers all of the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous sites and the Three Forks area of Montana. With the Grand Teton at its center, this area covers the richest beaver country in the Rocky Mountains.

Trade Goods:

The origin and destination of furs is shown on the fur trade map below. This map has been altered from the original by Mike White…some of the names were removed and others were enlarged.

During the early Indian fur trade period, the major articles traded to Indians for various furs and horses were: guns and ammunition, trade blankets, vermillion, silver, mirrors, knives, axes, beads, ribbons. thimbles, awls, cloth, copper kettles, sugar, and various pieces of horse tack. With the advent of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, the various trade articles brought to the rendezvous supplied both the Mountain Man and the Indians.

The price of trade goods were normally marked up at the rendezvous several hundred percent. In 1826, a prime beaver plew in the mountains had an approximate value of $3.00, by 1833 the value was $3.50, and by 1840, the value was $2.00 (Wishart). These values demonstrate why the trade good suppliers to the rendezvous made the money in the fur trade, not the trappers.

The 1826 agreement between William Ashley and the new firm of Smith Jackson and Sublette stipulated…Ashley or his agent would deliver to Smith Jackson and Sublette or to their agent at or near the west end of the little Lake of Bear River…the following items:

North West Fuzils [trade gun] – twenty-four dollars each

Gunpowder of the first and second quality – one dollar fifty per pound

Lead – one dollar per pound

Shot – one dollar twenty five cents per pound

Flints – fifty cents per dozen

Beaver traps – nine dollars each

Fourth proof rum reduced [?] – thirteen dollars fifty cents per Gallon

Bridles assorted – seven dollars each

Spurs – two dollars per pair

Horse shoes and nails – two dollars per pound

Three point blankets – nine dollars each

Green blanket – eleven dollars each

Two and a half point blankets – seven dollars each

Sugar – one dollar per pound

Coffee – one dollar twenty five cents pr pound

Flour – one dollar per pound

Alspice [allspice] – one dollar fifty cents per pound

Raisins – one dollar fifty cents per pound

Dried fruit – one dollar and fifty cents per pound

Scarlet cloth – six dollars per yard

Blue cloth common quality – four to five dollars per yard

Grey cloth common quality – five dollars per yard

Flannels common quality – one dollar fifty cents per yard

Calicos assorted – one dollar per yard

Domestic cotton – one dollar twenty five cents per yard

Thread assorted – three dollars per pound

Worsted binding [?] – fifteen dollars per gross pound

Finger rings – five dollars per gross.

Beads assorted – two fifty cents per pound

Vermillion – three dollars per pound

Hand kerchiefs assorted – one dollar fifty cents each.

Ribbons assorted – three dollars per bolt

Buttons – five dollars per Gross

Looking glasses – fifty cents each

Mockacine [moccasins] awls – twenty five cents per dozen

Tabacco [tobacco] – one dollar twenty five cents per pound

First quality James River Tobacco – one dollar seventy five cents per pound

Iron buckles assorted – two dollars fifty cents per pound

Butcher Knives – seventy five cents each

Files assorted – two dollars fifty cents per pound

Tin pans assorted – two dollars per pound

Fire steels – two dollars per pound

Copper kettles – three dollars per pound

Tin kettles different sizes – two dollars per pound

Sheet iron kettles – two dollars twenty five cents per pound

Squaw axes – two dollars fifty cents each

Steel bracelets – one dollar fifty cents per pair

Large brass wire – two dollars per pound

Washing soap – one dollar twenty five cents per pound

Shaving soap – two dollars per pound

It is interesting to note trade guns accounted for less than five percent of the trade goods.

The Hudson’s Bay Company used the “made beaver” as the unit of currency during the fur trade period. A made beaver was a prime beaver skin, flesh removed, stretched, and dried. The value of all trade goods was based on made beaver plews or pelts. The value of other furs, i.e. otter, fox, rabbit, martin, were valued in terms of made beaver. Eventually, the Hudson’s Bay and the North West companies issued tokens. The token value was based on the value of the made beaver.

Hudson’s Bay Company’s bead value for a made beaver:

six Hudson’s Bay beads

three light blue Padre beads

two larger transparent blue beads.

One Ordinary Riding Horse

8 buffalo robes

1 gun and 100 loads ammunition

1 carrot of tobacco weighing 3 lbs.

15 eagle feathers

10 weasel skins (Ermine)

5 tipi poles

1 skin shirt and leggings, decorated w/ human hair and quills

One Buffalo Robe

3 metal knives

25 loads of ammunition

1 large metal kettle

3 dozen iron arrow points

1/2 yards of calico

One fine racing horse = 10 guns

One fine buffalo horse = several pack horses

Three buffalo robes = 1 white blanket

Four buffalo robes = 1 scarlet Hudson’s Bay blanket

Five buffalo robes = 1 bear claw necklace

Thirty beaver pelts = 1 keg of rum [diluted]

Ten ermine pelts = 100 elk teeth.

During the summer months, the ermine’s color is brown with a yellow belly and is called a weasel.

Hudson’s Bay Six Point Blanket:

The Hudson’s Bay blanket was first introduced into the fur trade in 1780. The Witney weavers of Oxfordshire, England were the principal suppliers of Hudson’s Bay Blankets. The wool has always been a blend of varieties from England, Wales, New Zealand and India. The selected wool makes the blanket water resistant, soft, warm, and strong. Hudson’s bay blankets came in a variety of colors and patterns.

A point system is used to grade each blanket as to weight and size. The number of points were identified by five inch lines woven into the side of each blanket. The number of points represented the overall finished size of the blanket, not its value in terms of beaver pelts. Points ranged from one to six depending upon the size and weight of the blanket. The standard measurements for one point blanket was: eight feet in length, two feet and eight inches wide, and weighed three pounds and one ounce.

Statistical Review of the Mountain Man:

Richard J. Fehrman did a statistical evaluation of the 292 biographical sketches of mountain men that appeared in the ten volume Mountain Men Series edited by LeRoy Hafen and published by the Arthur H. Clark Company.

Of the 249 known birthplaces, four areas accounted for 53% of the trappers: Canada 38, Missouri 34, Kentucky 31, and Virginia 29. Thirty-one percent (78) were foreign born of these close to half were Canadians with the remaining coming from Europe or the British Isles. The average year of birth was 1805.

41% or 118 were free agents, or as many as with the first six leading companies combined. The term “free agents” signified that although he might be carried on a company roll, he could’ trap where he chose, either in a regular expedition or alone, but usually sold his furs to the company.

As to the marital status of the Mountain Men, there were 268 men whose status is known, Those who were married totaled 226, or 84% combined for a total of 304 known marriages. It is of interest to note that a further breakdown indicates that 140 or 62% married whites only; 63 or 28% married Indians only; and 23 or 10% married both whites and Indians. As near as can be determined about 34% of the white women taken as wives were of Mexican extraction. The majority of the children born to Mountain Men were born in wedlock. Of the 226 married trappers, 169 or 75% fathered 880 children, or an average of nearly four children per married subject.

The great majority – 134 or 58% of the known cases of these Mountain Men – died of old age or associated physical illnesses. Only 25, or 11%, of the subjects were murdered by Indians, while another 7% were killed by others than Indians. (If the study were to include all men who went to the mountains, the percentage killed by Indians would be greater. Regarding many of those who were killed, so little is known that no biographical sketches could be written – Dr. Hafen) Disease and illness accounted for the death of 38 or 16%, while eight or 3.5% were accidental deaths. The remaining 4.5% were due to suicide, alcoholism, and miscellaneous causes. Loss of life from the grizzly bear was minimal. Non-violent deaths accounted for about 77% of the cases.

Freeman made a composite picture of the average Mountain Man:

He was born in Canada in 1805, and was educated enough to be able to read and write. He left for the mountains in 1828 from St. Louis, and arrived at some point in the Rocky Mountains in 1830.

He traveled around the west, usually with his family, using horse or mule, or sometimes a bullboat. His wife cared for their three children as well as helping with many aspects of the trapping and fur preparation procedures.

When our man left the mountains in 1845, he turned to a career of farming or ranching. After leading a full life for 64 years, he passed away in 1869 as the result of old age or an associated illness. He was then laid to rest in the parts of the West where he had spent much of his life – Missouri and California.

The Mountain Man Indian Fur Trade article was written by Ned Eddins of Afton, Wyoming.

Permission is given for material from this site to be used for school research papers.

Citation: Eddins, Ned. (article name) Thefurtrapper.com. Afton, Wyoming. 2002.