|

Smoke Signals May/Jun 2012

|

||

|

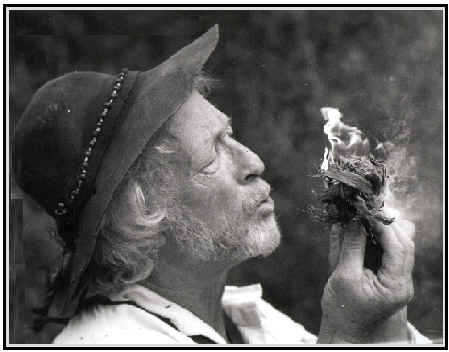

BILL

CUNNINGHAM |

Blowin' Smoke

|

|

|

WHEELS IN

THE WILDERNESS The

names of the original mountain men are often recalled during

conversations around rendezvous camp fires. Many times the names of

what today are the most famous are discussed: Meek, Bridger, Carson,

Williams, Wolfskill, Young, Yount, Fitzpatrick, Glass, Smith, and so

on. These were men of daring and courage, supposedly unexcelled in the

knowledge of survival and trapping. But there were other mountain men

as well practiced, as well admired by their peers, and perhaps even

more experienced. These were men widely known during the fur trade

days as ones to ride with, men who were often credited with teaching

some of the now better known men. And who knows why one man should be

longer remembered than another. Be that as it may, it really pays off

to research the journals, diaries, and letters from the era. Of course

there are shortcuts that can be taken by reading what has already been

written by biographers and historians. “He was

of medium height, stout frame , and fine face. He was full of humanity,

memory, an good will, genial feeling, and frankness. He possessed a

remarkable memory, and, though slow of speech, his narrations were

most interesting.” Another

friend, Jesse Applegate, described him this way:”Though Newell

came to the mountains from the State of Ohio in his youth, he brought

with him to his wild life some of the fruits of early culture which he

always retained. Though brave among the bravest he never made a

reckless display of that quality, and in battlefields as in councils,

his conduct was always marked by prudence and good sense. Though fond

of mirth and jollity and the life of social reunions, he never

degenerated from the behavior and instincts of a gentleman. Though his

love of country amounted to a passion and his mountain life was spent

in opposition and rivalry to the Hudson’s Bay Company, he never

permitted his prejudices to blind his judgement, or by word or act to

do injustice to an adversary.” Newell was

well traveled in the mountains and attended several rendezvous. Among

the companions he noted in his journal are Meek, Jed Smith, Robert

Campbell, Bridger, Jackson, the Sublettes, Moses Harris (who at one

time tried to murder Newell), Carson, Fraeb, Fitzpatrick, and others.

He was at Fort Hall often enough to be well known there and trusted.

He was referenced in the journals of several men as being at the sites

of numerous tangles with the Blackfeet. In one Meek tells of a tussle

Doc had with a wounded warrior he thought dead. Entwining his hand in

the Indian’s thick hair in order to scalp him, he was surprised by

the fellow suddenly coming around and grappling him. The two fought

furiously for a time, Doc’s fingers so entangled in the hair that he

could not let go. But eventually he won out, of course. A Mr. Elwood Evans later gave a

more detailed account of the trip as told to him by Doc. “Let me now

refer to the statement of the late Dr. Robert Newell, Speaker of the

House of Representatives of Oregon in 1848, a name familiar and held in

high remembrance by ancient Oregonians. It is interesting for its

history, and in the present occasion illustrates the difficulty, at that

time, of getting to Oregon. It details the bringing of the first wagon

to Fort Walla Walla, Oregon, in 1840, the Wallula of Washington

Territory. The party consisted of Dr. Newell and family, Col. Jos. L.

Meek and family, Caleb Wilkins of Tualatin Plains, and Frederick

Ermatinger, a chief factor of the Hudon’s Bay Company. It had been

regarded as the height of folly to attempt to bring wagons west of Fort

Hall. The Doctor suggested the experience. Wilkins approved it and

Ermatinger yielded. The Revs. Harvey Clark, A.B. Smith and P.B.

Littlejohn, missionaries, had accompanied the American Fur Company’s

expedition as far as Green River, where they employed Dr. Newell to

pilot them to Fort Hall. On arriving there they found their animals so

reduced, that they concluded to abandon their two wagons and Dr. Newell

accepted them for his services as guide. In a letter from the Doctor, he

says: “At the time I took the wagons, I had no idea of undertaking

these missionaries for their animals, and after they had gone a month or

more for Willamette and the American Fur Company had abandoned the

country for good, I concluded to hitch up and try the much dreaded job

of bringing a wagon to Oregon. I sold one of those wagons to Mr.

Ermatinger at Fort Hall. Mr. Caleb Wilkins had a small wagon which Joel

Walker had left at Fort Hall. On the 5th of August (September

27) 1840, we put out with three wagons. Joseph L. Meek drove my wagon.

In a few days we began to realize the difficulty of the task before us,

and found that the continual crashing of the sage under our wagons,

which was in many places higher than the mules’s backs, was no joke.

Seeing our animals begin to fail, we began to light up, finally threw

away our wagon beds, and were quite sorry we had undertaken the job, All

the consolation we had was that we broke the first sage on that road,

and were too proud to eat anything but dried salmon skins after our

provisions had become exhausted. In a rather rough and reduced state, we

arrived at Dr. Whitman’s mission station in the Walla Walla valley,

where we met that hospitable man, and kindly made welcome and feasted

accordingly. On hearing me regret that I had undertaken to bring wagons,

the Doctor said,’O, you will never regret it. You have broken the ice,

and when others see that wagons have passed they too will pass, and in a

few years the valley will be full of our people.’ The Doctor shook me

heartily by the hand; Mrs. Whitman too welcomed us, and the Indians

walked around the wagons, or what they called “horse canoes,” and

seemed to give it up. We spent a day or so with the Doctor and then went

to Fort Walla Walla, where we were kindly received by Mr. P.C. Pambrum,

chief trader of Hudson’s Bay Company, superintendent of that post. On

the first of October we took leave of those kind people, leaving our

wagons and taking the river trail - but we proceeded slowly.” Ref:

Leroy R. Hafen: Mountain Men and the Fur Trade vol. VIII Bill Cunningham NAF #006 |

||