|

Smoke Signals Mar/Apr 2012

|

||

|

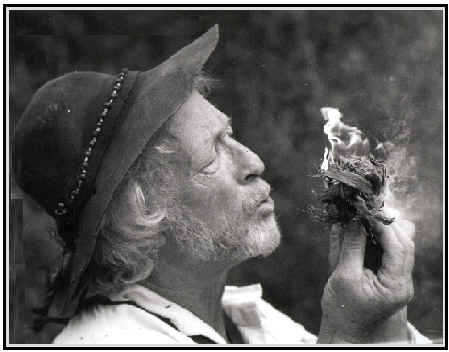

BILL

CUNNINGHAM |

Blowin' Smoke

|

|

|

Blowin' Smoke

WERE ONLY TRAPPERS “MOUNTAIN

MEN”?

History records quite a number of men who, during the fur trade years, traveled to the Rockies yet never belonged to a fur brigade, were not considered free trappers, and never worked as trappers for the HBC or the AMC. From time to time they may have done some trapping, but if so it was only for lack of something else to do, was not done in employment for anyone but themselves, and lasted but for a short while. Men such as Miles Goodyear, James Kipp, and Mathew Kinkead fit in this category. I’m betting that of the three you have only heard of Miles Goodyear, even though he died at the fairly young age 32 and the others lived long lives. Such are the vagaries of history and circumstance. During his life Mathew Kinkead

was later perhaps best known for, at his home in Taos, taking in the

young Kit Carson shortly after Carson had taken leave of an abhorred

apprenticeship back east. Perhaps because of Carson’s later

reputation Kinkead, who had a life of broad experiences in the

southwest, became generally known only for his hospitality. But he

was much more than that. James Kipp, on the other hand,

never spent time in the southwest. He originally came from near

Montreal. Beginning about 1808, when he was 20, he worked as a

hunter and trapper in the Red River region but evidently on his own.

By the time he was thirty he was on the upper Missouri working for

the Columbia Fur Company as an agent. This was in 1822 and a year

later, still as an agent, he went up the Missouri to the Mandan

villages. Kipp was known as an educated man. Supposedly he was the

only white man to learn the Mandan language and it was here near the

Mandans that he earned the reputation as a builder of fur-trading

posts—fort structures designed as much for protection as for

trade. In 1826 a man named Tilton arrived and took charge of the

post and Kipp went up to the mouth of the White Earth River and

built another post. While Kipp was maturing and

then building posts, Mathew Kinkead was doing some growing of his

own. Hauled along by his father, David, and in company with his

step-mother and seven siblings, from Kentucky to the Femme Osage

River in Missouri in 1803, and shortly after to the forks of the

Charette to a land-grant from the governor. In 1809 the grant was

rescinded for some unexplained reason, and David took the family to

Boone’s Lick. When the War of 1812 broke out the Kinkead family

got to live in close quarters in forts with many others, some who

became quite famous in the history of the west: people like Josia

Gregg, William Wolfskill, Kit Carson, James Cockerell, Stephen

Cooper (who opened the trade with Santa Fe in 1821), and many others

who later became Santa Fe traders. David Kinkead built a fort on the

Missouri River and 29 men and boys survived the three years of war

there, having many skirmishes with the Indians. By 1828 the Columbia Fur

Company had merged with the American Fur Company and Kipp was hired

by the company to build Fort Floyd, later Fort Union. He stayed

there until early 1831. During that time he built Fort Clark by the

Mandan villages. The following winter he built Fort Piegan among the

Blackfeet above the mouth of the Marias River. But despite his post/fort

building, Kipp’s major assignments, however, seemed to have been

to take furs and skins gleaned from the Indian trade down the river

to St. Louis each year from whence he turned around and went back to

Indian country. Usually, when he arrived there, he was put in charge

of one or more of the Company’s posts, By December of 1830, Kinkead

was a naturalized citizen of Mexico and still operating the whiskey

mill. However, in late 1835, he received a land grant of two hundred

varas of land in the Santa Gertrudes valley (present Mora, New

Mexico). Here he settled for a time. During this period he began

keeping house with a strikingly beautiful woman, Maria Teresa (Teresita)

Suaso, With this strong willed and jealous mate he had two children.

By 1841 had left Mora and moved to the present site of Pueblo,

Colorado. In the spring of that year, Dick Wooten drove a flock of

Kinkead’s sheep to what is now Kansas City (Westport at the time)

and sold them. Things get a bit cloudy here, but perhaps the two

used the profits to go into the buffalo business. Wooten caught up

nearly 50 buffalo calves and turned them in with a corral full of

cows. When the calves were three years old, Wooten drove them back

to Westport and sold them. For a while there was a terrific market

for what back east were interesting novelties. By 1841, Kipp was stationed at

Fort Union where he was met by Father deSmet. The priest noted that

Kipp was the principal administrator there and was favorably

impressed by him. John Audubon and Ed Harris met him and described

him as one of the partners of the Upper Missouri Outfit. This was in

1843. Kipp provided Audubon with lots of specimens and information

about the area. He left them to travel up the Yellowstone to take

charge of Fort Alexander but by 1846 he was back in charge of Fort

Union. He met there Charles Larpenteur who was then out of work. In the spring of 1849 Kinkead,

in company with John Brown, Jim Waters, and others, moved to

Sacramento where he became quite wealthy. He owned ships, land and

haciendas. Just when he died is not noted, but in 1878 his son

Andres (now Andrew) went back to New Mexico to sell his father’s

Mora Grant land, some lots in Taos, and some property in Salt Lake

City. While in New Mexico he visited his 91 year old mother. She

died the next year. Probably still cranky. Kipp left the fur trade about

1865 and moved to his farm in Missouri. In July, 1880 he died and

was buried at Parkville.

Bill Cunningham NAF #006 |

||