|

MILLER

- CATLIN - BODMER

Among the

artists who first recorded the American West the most important

are George Catlin, Karl Bodmer, and Alfred Jacob Miller in this

order. Of this

group, Catlin and Bodmer were motivated primarily to produce a

historical and ethnographic record and were imbued with an

essentially scientific point of view. Miller is a different

matter. To compare him with Catlin and Bodmer is to juxtapose

passionate sincerity, professional objectivity, and romantic

poetry, which, in all fairness, are hardly comparable.

Miller

was trained in Paris and Rome in portrait, landscape, and marine

painting as well as that most romantic of themes, the painting

of history. His great opportunity came to accompany the wealthy

Scottish traveler Sir William Drummond Stewart on a tour of the

trans-Mississippi West, he was to record, not the facts of

ethnography, but a dramatic adventure into an exotic world.

In regard to

the paintings of Catlin and Bodmer; they are viewed as exciting

early views by white people of the Indian cultures, showing the

customs, costumes, and physiognomy. The look of things before

they would be changed forever.

Miller was

born in Baltimore. He studied in Paris and Rome, upon his return

to this country he opened a portrait studio in Baltimore but was

unsuccessful. In 1837 he moved to New Orleans where he was

selected by Capt. William Drummond Stewart as artist to record a

journey to the Rocky Mountains. The expedition journeyed by

wagon along what was to become the Oregon Trail. Miller sketched

the Native American along the way and also recorded the

rendezvous of the mountain men in what is now southwestern

Wyoming. Miller returned to Saint Louis with about 166 sketches

which were later developed into oil paintings while in New

Orleans and Baltimore. From 1840 to 1842 he lived in Stewart's

Murthly Castle in Scotland, Painting oils as decorations

depicting favorite episodes from the trip. He also delivered a

portfolio of 83 small drawings and watercolors. Miller spent the

rest of his life in Baltimore painting portraits and making

copies of his Western themes.

One

of the best known paintings in Joslyn's extensive Miller

collection, The Trapper's Bride represents an American

Fur Company trapper taking a wife. Miller painted several

versions of this subject, one of which is in the Walters Art

Gallery in the artist's home town. About this incident the

artist later wrote:

The

price of acquisition in this case was $600 paid for in the

legal tender of the region: viz.: Guns, $100 each, Blankets

$40 each, Red Flannel $20 pr yard, Alcohol $64 pr. Gal.,

Tobacco, Beads etc. at corresponding rates. A Free Trapper is

a most desirable match, but it is conceded that he is a ruined

man after such an investment.... The poor devil trapper sells

himself, body and soul, to the Fur Company for a number of

years. He traps beaver, hunts the Buffalo and bear, Elk, etc.

The furs and robes of which the Company credits to his

account. - David

C. Hunt

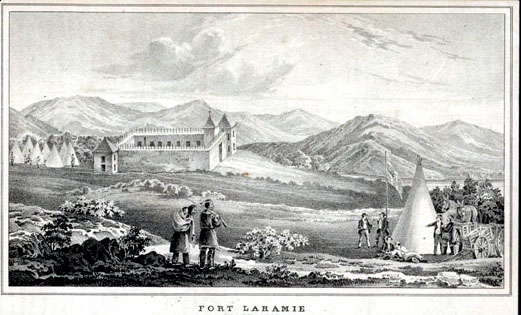

Fort Laramie, 1845

Ft. Laramie

has in its history four incarnations: (a) a cottonwood stockade

constructed at Laramie's Point, but named by Wm. Sublette "Fort

William", 1837 painting by Alfred Jacob Miller shows

the exterior view; an adobe fort depicted in the

engraving; a military post, showing its present configuration

consisting of a mix of restorations and ruins. The fort served

as a terminus of the "Trappers' Trail running from Taos

northward. The Trappers Trail fell into disusage when fashions

changed and silk replaced beaver in hats. In 1841,the stockade

was replaced by an adobe structure depicted in the engraving

above and as described by Francis Parkman below.

Miller gave a description

of the fort as being: "of

a quadrangular form, with block houses at diagonal corners to

sweep the fronts in case of attack. Over the front entrance is a

large blockhouse in which is placed a cannon. The interior of

the fort is about 150 feet square, surrounded by small cabins

whose roofs reach within 3 feet of the top of the palisades

against which they abut. The Indians encamp in great numbers

here 3 or 4 times a year, bringing peltries to be exchanged for

dry goods, tobacco, beads and alcohol. The Indians have a mortal

horror of the "big gun" which rests in the blockhouse,

as they have had experience of its prowess and witnessed the

havoc produced by its loud "talk". They conceive it to

be only asleep and have a wholesome dread of its being waked up."

_______________________________________________________________

Bodmer

was born in Zurich, Switzerland. At the age of thirteen he began

to study art with his uncle Johann Jakob Meier; a painter and

printmaker. In 1828, Karl and his elder brother Rudolph left

Switzerland and followed the Rhine to Koblenz where they began

to work on their own. Bodmer worked there for three years,

producing drawings and sketches that were etched by Rudolph and

sold to tourists in travel albums. It was while he was in

Koblenz that the young Bodmer met Prince Maximilian in January

of 1832. The Prince was planning a trip to North America and was

looking for an artist to illustrate his travels Bodmer served

the expedition in much the same way as a modern-day

photographer. His landscapes recorded the western frontier so

accurately that the landmarks—where they have not been altered

by time or settlement—are identifiable today. And his detailed

portraits of Native Americans are among the most important

visual records of the Plains Indian tribes in the early 19th

century.

Places

visited by Prince

Maximilian and Karl Bodmer:

Europe

to St. Louis, May 17, 1832 - March 24, 1833

On

May 17, 1832, Maximilian and Bodmer boarded the Janus and set

sail from the Netherlands. They arrived in Boston on July 4,

1832, amid Independence Day celebrations. From there, they

traveled by stagecoach into New York City and across

Pennsylvania, stopping to visit in Philadelphia, Bethlehem. They

continued west through Ohio and into Indiana [Mouth of Fox

River, (Indiana)], spending the winter in New Harmony,

Indiana so Maximilian could recover from illness. Thomas Say and

Charles-Alexander Lesueur had been on two American frontier

expeditions with Major Stephen Long who, a decade earlier,

explored the Rocky Mountains; Lesueur was respected for his

study of living organisms in Australia as well as North America.

Maximilian took advantage of this opportunity to visit with the

scientists, and utilize the town's library that contained one of

the best natural history collections in the country. In the

spring, the journey continued by riverboat to St. Louis,

Missouri, which served as the gateway to the west.

St.

Louis to Fort Union, March 24 - July 6, 1833

In

April, Maximilian and Bodmer boarded the American Fur Company's

steamboat, Yellow-Stone,

to

begin their historic journey up the Missouri River. In early

May, the Yellow-Stone docked at Bellevue, located just south of

present-day Omaha, Nebraska, where Maximilian and Bodmer visited

a trading post and Indian agency operated by Major John

Dougherty. The party continued upriver to Fort Pierre where they

boarded the larger steamboat, Assiniboine. Seventy-five days

after leaving St. Louis, the expedition reached Fort Union, in

present day North Dakota, [Fort Union on the Missouri]

which was the farthest a steamboat could navigate on the

Missouri at this time. Like the other Missouri River forts

visited by Maximilian and Bodmer, Fort Union was not a military

encampment but a commercial outpost owned by John Jacob Astor's

American Fur Company and operated for trading purposes.

Fort

Union to Fort McKenzie, July 6 - September 14, 1833

In

order to push further west, Maximilian's party boarded a Fur

Company keelboat and traveled another 500 miles upstream toward

Fort McKenzie, north of what is now Great Falls, Montana. While

traveling on the upper Missouri, they passed through a

particularly beautiful area of the Missouri River where Bodmer

depicted the Stone Walls on the Upper Missouri.

Winter

at Fort Clark, November 8, 1833 - April 18, 1834

After

spending six weeks at Fort Mckenzie, the expedition returned

downriver to Fort Clark, located about 45 miles north of the

present city of Bismarck, North Dakota; they wanted to meet and

learn more about the Mandan and Minatarre [Hidatsa], whose

villages were located near the post [Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch, a

Mandan village]. They spent an extremely bitter winter of

1833-1834 at the fort where they endured many hardships. In

spite of this, however, the two men continued their work with

great interest and in good spirits. Maximilian collected

information from the warriors and elders of the tribe; and

Bodmer executed dozens of studies of the villages, ceremonies,

and individual people.

St. Louis to New York - May 27 - July 14. On April

18 the party left Fort Clark and proceeded downriver, landing at

St. Louis on May 27. Their journey back to New York took them to

the Great Lakes and to Niagara Falls. They sailed for Europe on

July 16. Maximilian and Bodmer took with them vast numbers of

specimens of flora, fauna (including live bears!), densely

packed pages of notes, and many sheets of detailed drawings and

watercolors produced during the journey.

Bodmer

was employed to make detailed, accurate drawings of what the two

men saw on their expedition, to be used upon their return to

Europe to generate the printed illustrations for the account

Maximilian planned to publish of their experiences. As they

journeyed across the eastern half of the United States,

Maximilian recorded numerous insightful observations about the

young nation. But Maximilian and Bodmer's most notable

contributions lie in their ground-breaking documentation of the

flora, fauna, and native inhabitants of the Missouri River

valley, from St. Louis to Montana. Maximilian's diary records

the life, rituals and languages of tribes such as the Omaha,

Sioux, Assiniboin, Blackfoot, Mandan, and Minatarre (commonly

known as Hidatsa). Bodmer's work vividly reflects the

landscapes, wildlife, frontier settlements, Indian villages, and

people that Maximilian described in his diaries. Together,

Maximilian and Bodmer's written and visual documentation

constitute an invaluable record of the upper Missouri frontier.

In

1834 the steamboat Assiniboin, carrying a large part of Prince

Maximilian's natural history and ethnographic specimens burned

and sank on the Missouri River.

Following

the Buffalo: In the 1830s the buffalo was the staff of

life for the Plains Indians, providing food, clothing, and

shelter. A full-grown bull at 8 to 10 years old measured six

feet tall at the shoulder, 10 feet long from nose to rump, and

could weigh as much as 2,000 pounds. Maximilian and Bodmer

witnessed a large number of buffalo moving toward the river

while traveling from Fort McKenzie to Fort Union. Bodmer

captured the scene in Herds of Bisons and Elks on the Upper

Missouri.

While visiting Fort Union on their way up the Missouri River,

Maximilian and Bodmer recorded the life of the Assiniboins, a

nomadic tribe encamped in the area. Maximilian visited the

Assiniboin camps, observing the women at work, a curing

ceremony, and other aspects of tribal life. He describes in his

journal their patterns of nomadic movement and methods of

hunting:

The two explorers spent twelve days at the fort where Bodmer

rendered portraits of Assiniboin tribesmen and scenes of daily

life. His work there includes a sketch that became the print A

Skin Lodge of an Assiniboin Chief which shows a tipi made of

buffalo hide.

_______________________________________________________________

Catlin's Letters

and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North

American Indians read. "If I should live to

accomplish my design, the result of my labours will doubtless

be interesting to future ages; who will have little else left

from which to judge of the original inhabitants of this simple

race of beings, who require but a few years more of the march

of civilization and death, to deprive them all of their native

customs and character."

Early

exposure to Indian lore may have sparked George Catlin's

lifelong interest in native American culture. In a frequently

quoted, albeit highly romanticized, autobiographical account,

the artist related colorful tales of his mother's capture and

safe return by a band of Iroquois and his own vivid memories

of a friendly Oneida tribesman who was murdered when Catlin

was about ten years old. Nearly two decades later, the legend

continues, a chance encounter with a delegation of Plains

Indians passing through Philadelphia rekindled the artist's

youthful fascination. Inspired by their pristine grandeur,

Catlin dedicated himself to the monumental task of documenting

all Indian tribes from the Alleghenies to the Rockies, vowing

nothing short of the loss of his life would prevent him from

visiting their country and becoming their historian.

Catlin's professional life was somewhat unorthodox. Acceding

to his father's wishes, he agreed to study law in Litchfield,

Connecticut, but concurrently established a more

temperamentally congenial alternative career as a painter of

portrait miniatures. After passing the bar exam in

Connecticut, Catlin returned home to rural Pennsylvania, where

he practiced law with his older brother for three years.

By 1821 the young artist had moved to Philadelphia, where he

exhibited some early work at the Pennsylvania Academy of the

Fine Arts. Catlin remained in the city for approximately four

years and probably undertook some formal art study during this

period, but little definitive information exists regarding his

early training. He was invited to Albany to paint

DeWitt Clinton, the governor of New York, in 1824 and the

following year he was hired to create a series of lithographs

depicting construction sites along the Erie Canal.

Catlin settled in New York in 1826, the year he

was elected to the National Academy of Design. Although work was scarce

during much of this time, in 1829 the artist did receive a

relatively prestigious commission to paint a group portrait of

the one-hundred-one Virginia legislators assembled at the

State Constitutional Convention in Richmond.

Despite this minor coup, Catlin was becoming increasingly

dissatisfied with the progress of his career. After more than

a decade as a painter, he had attained only marginal success.

Like many artists of his day, Catlin believed that history

painting would be a far more elevated vehicle for his creative

talents than portraiture; yet, when forced to vie for

patronage with more established -- and more skilled--

contemporaries, he had great difficulty obtaining commissions

for this type of work. Stung by harsh criticism of his

painting by influential critics such as William Dunlap, who

described him as "utterly incompetent," Catlin may

have began to doubt his ability to compete with better-known

artists. Surely, he must have realized that an alternate,

highly unconventional career spent traveling throughout the

western territories painting Indians would offer him adventure

and almost certain fame, since regardless of the critical

evaluation of his art in purely aesthetic terms, the

historical significance of his pioneering contribution could

not be denied.

With the aid and encouragement of General William Clark, the

renowned explorer who was then serving as Superintendent of

Indian Affairs for the Western tribes and Governor of the

Missouri Territory, the artist gained access to numerous

midwestern tribes and was able to study them in great detail.

Scholars differ widely as to the chronology of his travels,

and Catlin's own itineraries --reconstructed in later years--

often are unreliable. It is known that the first Indian

portraits he painted in the West were executed near Fort

Leavenworth in northeastern Kansas in the late summer or early

fall of 1830. After a season of intensive field work during

which he produced numerous summary sketches, Catlin returned

east in the late fall, visiting New York, Albany, and

Washington. Rather than traveling extensively the following

year, he probably spent most of 1831 finishing paintings based

on the field studies he had created the previous season.

Catlin was anxious to

travel even further west, seeking even more distant Indian

tribes that presumably were less likely to have been

compromised by their contact with white men. He returned to

Saint Louis in December, 1831, and the following spring he

undertook an arduous three m onth journey on the Yellowstone

River to Fort Union, North Dakota, two thousand miles upriver.

During the voyage, Catlin painted landscapes from the deck of

the steamboat, and after arriving at his destination, he began

painting genre scenes of Indian life in addition to

straightforward portraits. He kept extensive notes to document

his travels and made numerous notebook sketches.

While in the Upper Missouri territories, the prolific artist

often completed five or six paintings a day. Returning south

with French-Canadian trappers, he visited the Mandan villages,

where he was permitted to witness and document a sacred four

day initiation ceremony. Some scholars have suggested that

Catlin's month long, in-depth study of the now extinct Mandan

tribe constitutes his greatest ethnographic achievement. In

the summer of 1838, only six years after his visit, the Mandan

Indians were virtually annihilated by a smallpox epidemic

inadvertently introduced by fur traders. Catlin reported that

nearly half of the contaminated Indians, realizing that death

was inevitable, "destroyed themselves with their knives,

with their guns, and by dashing their brains out by leaping

head-foremost from a thirty foot ledge of rocks in front of

the village." Within months, nearly two thousand had

perished. The forty who survived the epidemic were soon

enslaved, murdered, or assimilated by neighboring tribes. The

virulent disease ravaged adjacent tribes, as well, killing

some 25,000 Blackfoot, Cheyenne, and Crow Indians before

gradually spreading west to the Pacific, leaving a trail of

death and devastation in its wake. Appalled by the tragic

loss, Catlin lamented, "What an illustration is this of

the wickedness of mercenary white men. "

Contrary to information

the artist published years later, Catlin probably did not

travel west in 1833; he most likely took time off to complete

works begun the previous season. He exhibited some one-

hundred-forty paintings in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and

possibly Louisville that year, and he may have spent part of

the winter in New Orleans. In the spring of 1834 Catlin

accepted an invitation to join the first U.S. military

expedition to the Southwest, where he encountered little known

tribes such as the Comanche in Oklahoma. During this arduous

journey, the artist -- along with many in his party-- became

seriously ill with fever. More than a hundred in the group

died. After several weeks of recuperation at Fort Gibson,

Catlin made a solitary twenty-five day, five hundred fifty

mile trip back to Saint Louis on horseback. He and his wife,

who had been living there with friends during her husband's

extended absence, sailed to New Orleans, before moving on to

Pensacola, Florida, where they visited one of his brothers for

the winter. He returned to New Orleans, where he lectured and

exhibited some work in the spring of 1835. Catlin then

traveled north to Fort Snelling (on the Upper Mississippi near

St. Paul, Minnesota), where he painted the Ojibwas and Eastern

Sioux. He also traveled in Iowa that year, painting Sauk and

Fox Indians.

Catlin shipped his art east and began planning an exhibition

for the late spring of 1836. His wife, who was expecting their

first child, had returned to be with her family in Albany.

When she suffered a miscarriage, Catlin abruptly cancelled the

scheduled Buffalo show and in June set out in search of the

Pipe Stone Quarry in southwestern Minnesota, a legendary site

where Indians of many nations garnered material for their

peace pipes. Formerly this land had been considered neutral

territory -- a sacred place where enemies could meet in

harmony in accordance with the wishes of the Great Spirit. By

the time of Catlin's visit, however, it was controlled by the

Sioux, who detained the artist and his English traveling

companion in an attempt to restrict their access. Catlin

persevered, however, even managing to collect some of the

prized mineral, which later was named "Catlinite" in

his honor.

_______________________________________________________________

There

is so much more information available on the Internet, in

libraries and book stores on these gentlemen that this is just a

very small sampling to make you aware of these sources at hand.

Use them, you will enjoy the experience of those that have

traveled before you. Hope you enjoyed this short history of

these wonderful artists that have recorded our history in their

work.

come warm yourself friends

come warm yourself friends

stay

and enjoy yourself,

we like the company.

|